It's that time of year again. The time of the year that you see the new interns scrambling through the department, eyes wide as saucers, running scared, and hungry for experience. As an educator, it's a refreshing time to be at work!

With the start of the interns, many blogs have been providing advice to help them on their way to a successful career. Some of the better examples are here and here.

But this is emergency medicine, and while the given advice still applies, I wanted to add a little more, just for our learners. When I began my residency, one of our attendings handed us a copy of "The Ten Commandments of Emergency Medicine." I still have my original copy and now and then I hand it out to my residents. As I dusted it off this year, I realized that the article was written in 1991! Are the commandments still relevant? Read on. . .

Secure the ABC's

Relevance: High

We pride ourselves on being the masters of resuscitation. Mastering the patients' ABCs should be the priority the moment you walk in the room. Simply walking in and observing your patient can give you an amazing amount of information. Is the patient able to speak full sentences? Are they talking at all? Do they make sense? How is their color, work of breathing, pulse, etc? If you find a problem, fix it first.

The authors of the article expand the ABC's mnemonic a little ABCD2EFG2. While most of these are familiar to us, the addition FG2 is useful to remember:

Fetal Heart tones: a needed vital sign in pregnant patients

RhoGam: Consider getting the type and Rh in pregnant trauma patients

Guardrails: Confused and elderly people fall out of bed far too often. If you put them down or find them down, then take the 10 second and put them up!

Consider or give naloxone, glucose, and thiamine

Relevance: Glucose, high; others moderate

Any patient with altered mental status or a new neurologic deficit deserves a fingerstick glucose. Almost every one of us has forgotten this truism once. The embarrassment experienced by performing the stroke workup only to get the critical glucose level back from the lab is never forgotten

As for naloxone, consider it, but give it in smaller doses if you give it at all. Remember "Priumum non Nocere." After witnessing an addict in iatrogenic withdrawal once, I'm more likely to give 0.2 to 0.4 mg or simply intubate the patient and wait.

Thiamine is safe and potentially helpful. While we still give it to the patient with alcoholism, the population that seems to need it the most these days are the post-gastric bypass population.

Get a pregnancy test

Relevance: Very High

I remember a story about a seasoned senior EM attending being asked what the biggest development of his career was. The answer? The urine pregnancy test. Any female, age 10-55, deserves this quick test. You'll lose count of how often your workup will be changed by the results of this test.

Assume the worst

Relevance: Very High

Amal Mattu likes to quip, "When emergency physicians here hoofbeats, we think lions, and tigers, and bears." We aren't after the zebras. Whatever can kill the patient we rule out first. Only then do we move on less severe and more likely conditions. Check your attitude at the door. Don't get hung up on the 20/10 pain while the patient sits eating a bag of chips. Take them at their word, do your best exam, and give them the benefit of the doubt. You will be humbled time and time again by the seemingly stable patient who tries to die, sometimes successfully, in front of you.

Do not send unstable patients to radiology

Relevance: Moderate

This is one area that has changed in recent years. It no longer takes as long to get studies done, and sometimes that septic elderly patient will need a CT to find the phlegmon of infection. I would change the commandment to: Do not send unstable patients to radiology alone; you must go with them. If conditions exist which can be fixed first then do so: secure the airway, begin fixing volume problems, etc. If an alternative exists, such as bedside ultrasound, use it to your advantage, but don't fail to make the diagnosis simply to avoid taking the patient out of the department. Oh yeah, and when you take them, take the right equipment too.

Look for common red flags

Relevance: High

I always get a little but of a laugh when reading this one. It talks about FOUR vital signs! With pulse ox and capnography and pain (really?) we have more vitals than we know what to do with! The point is simple: look at the vitals and explain them. Your history will gain you more than an entire battery of labs. Ask about comorbidities. Ask about risk factors; that patient with an IV drug addiction who has back pain and a low grade fever isn't looking to score narcotics. Remember the extremes of age. Pay particular attention to revisits. These patients are giving you a second or third chance to make the correct diagnosis. And remember, before anyone goes home, they must be able to eat and walk.

Trust no one, believe nothing (not even yourself)

Relevance: High

Anything that any tells you, in person, or in writing, might be false. The "frequent flier" may be in the department often, but also might have real disease. Always start with a open mind, talk to the patient, examine the patient fully, and look at every image and study yourself. Remember, the cardiologist and radiologist aren't seeing the patient and can miss significant findings.

The same advice applies to your teachers, and to this post. Be skeptical but not cynical. Take the time to check the facts, read the literature yourself, and try both old and new techniques. Did you find an absence of evidence about a treatment? You may have just found your research project!

Learn from your mistakes

Relevance: High

I've learned far more from my mistakes than my successes. We all make mistakes. The important part is to learn from them. Possibly even more important is learning OF them. Emergency medicine is particularly prone to an absence of feedback about our mistakes. Did you have an uncertain diagnosis? Look into the case and follow up on the patient after discharge. Learning about our errors is essential to improving our practice.

Since we all make them, try not to judge others by their mistakes. Learn from their errors, but look deeper as well. Were there any system issues, communication errors, etc, that may have contributed to the error? Can any of these be fixed to prevent the error from occurring again?

Do unto others as you would do to your family (and that includes coworkers)

Relevance: High

You'll more often do the right thing when you follow this maxim. Respecting our patients, colleagues, and coworkers demonstrates the caring attitude expected of a good physician. And remember this if you decide to be rude: "The toes you step on today might be connected to the backside you need to kiss tomorrow."

When in doubt, always err on the side of the patient

Relevance: High

We see the patients that society and even healthcare tend to forget: the homeless, the addicted, the psychiatric, etc. We need to be the ultimate patient advocate. We strive to relieve suffering. To do what is right for the patient, we need to consider the course of action that would minimize their suffering and keep the patient safe. This will unfortunately put us at odds with our administrators, and at times, our peers, but if we fail to take care of our patients, then no one else will either and we will have violated our sacred oath.

As you can see, despite being 20 years old, these "commandments" still have a significant amount of relevance today. For sure, they could be added too, but for the start of your career, paying attention to this short list will help you to save lives become a better emergency physician.

Thursday, July 7, 2011

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Stick with the Herd?

Knowing is not enough. We must apply.

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Recently, the crew recorded a debate between Mel and Billy Mallon about the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol for Atrial Fibrillation. During his rant, Dr, Mallon makes some important criticisms of the protocol. If he had stuck with his numbers, he would have made a convincing argument against the protocol. But then, he blunders. As an educator, he makes a statement to his residents and students that I see as irresponsible of an educator.

It goes as follows:

"My top 10 reasons for not doing this are: 1. Most don't. And just as an idea in medicine and a concept: stay within the herd. If you want to know what the problems are of not being in the herd, turn on the nature channel. The gazelles that are not in the herd, are lion food. Okay? Stay with the herd! The herd doesn't do this."

Really? REALLY? An idea and concept? That's the number 1 reason? Do what everyone else does? That sounds more like lawyer speak than physician speak. Almost like when I overheard a fellow faculty member tell a resident to get ankle x-rays on a Ottawa negative patient "because this isn't Canada; Canadians don't get sued."

The "go with the herd" mentality is a dangerous preposition in medicine. Medical history is filled with vivid examples of how patients were harmed because the this mentality. Virchow, the leading authority in his time, was particularly critical of Ignaz Semmelweis and his data to suggest that physicians could cut disease rates by simply washing their hands. Who knows how many lives were lost due to the fact that physicians were "gentlemen" and felt that they didn't need to wash their hands. 160 years later, we're still dealing with the fallout.

Why is it that interventions known to be effective take so long to put into practice. Herd mentality. If nobody else does it why should I? There is an old joke in medicine that you don't want to be the first to do something. But, you also don't want to be the last.

As educators, we have a responsibility to be second or third. We need to be early adopters and try out new ways of taking care of patients especially when the literature shows some support. We need to take what others have done and reproduce it, testing it with our learners and demonstrating that science constantly changes. Even more, we need to measure our results and disseminate them with time. Only then can we advance the care of our patients.

Take the Ottawa Protocol, for example. I've used it for 4 patients now with a 75% success rate. To be fair, I haven't sent the patients home. We don't have the most reliable outpatient followup. That being said I've managed to admit patients to beds without the need to advanced monitoring since they didn't need vaso-active drips and have kept them off of the nastiest of nasty drugs, warfarin.

And that is only one example of a countless list. The last 2 decades have shed light on the failure of medicine to adopt treatments that benefit society. We have become far more capable of creating knowledge than using it. Perhaps our fear of leaving the herd is partially responsible for this failure.

So lets change it. Let's take the time to venture outward, leading the herd. Let's generate knowledge and take time to test it, apply it, and teach it.

What of the risks? Remember, when you lead the herd, you don't need to outrun the fastest lion, only the slowest gazelle. You're never alone out there!

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

The Academic Practice of Wilderness Medicine?

The recent Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting just concluded after several fun and learning filled days in Boston. I was fortunate to be able to attend and learn from the best and the brightest.

One of the presentations that stands out in my mind was a panel discussion about the "Academic Practice of Wilderness Medicine." Wilderness medicine probably got me into medicine to begin with. In my teen years, I was a member of a Venture Crew and spent many hours learning to climb, kayak, and haul a pack. Our leader was a former paramedic and encouraged several of us to pursue training as EMTs to be better prepared for handling emergencies in the outdoors. Thus began my love of emergency and wilderness medicine.

Being in a community academic site, I've always put wilderness medicine onto the back burner thinking that I didn't have the skills or resources enough to make it into a viable niche. This presentation, given by Sanjay Gupta, N. Stuart Harris, and Michael Millin, was a nice summary of the growing field and has rekindled my interest in wilderness medicine.

First, what is wilderness medicine?

At its most basic, it is the practice of medicine in austere environments. While generally thought to represent the out-of-doors, this can encompass military settings, event medicine, disasters, and other less than ideal settings.

How do you start in wilderness medicine?

There are many ways to get started. As an academic, we're always looking to cement our niche. Probably the most basic way to do this is training. Fellowships now exist in many places that are dedicated to wilderness medicine or wilderness medicine and EMS. For those who have already graduated, there are any number of courses, seminars, and experiences available to build your expertise. The Wilderness Medical Society even has a fellowship track for physicians to demonstrate a level of expertise within the field.

But what makes it Academic?

Here is where the presentation got interesting. I've always thought of academic practice within this field as being research based; high altitude medicine, tropical diseases, etc. Like many academic pursuits, there is so much more to practicing wilderness medicine. You can, for example:

- Become the faculty mentor for a wilderness medicine interest group

- Teach at medical schools, residencies, or CME courses

- Become a military, expedition, or event consultant

- Serve as a medical director for a search and rescue team

- Serve as a travel medicine consultant

- Actually become a researcher

- Participate in the leadership of Wilderness Medicine oriented committees, interest groups, or the WMS

At SAEM, we became a fully fledged interest group at the meeting. We even were able to head to the nearby quarry for an afternoon of learning the basics of high angle rescue. The excitement on the participants faces as they took that first uncertain step into the air during their rappel was a priceless reminder of why I love teaching and emergency medicine.

Having had my assumptions challenged and realizing that there are opportunities for developing an academic niche in wilderness medicine even at a community site, you can expect to see more on various topics related to Wilderness Medicine in the future!

I would like to thank N. Stuart Harris for his leadership over the last year, his vision to start the interest group, and his willingness to share his rope, local crag, and experience with us this past week.

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Another Satisfied Customer?

Do you believe in patient satisfaction? For the majority of my training, I had my doubts. As an impressionable intern, I remember a conversation between 2 seniors discussing a patient complaint about the wait. The conclusion was something like this: "This isn't Burger King. In the ED, you don't get it your way, right away." For a long time, I believed that good care comes first and satisfying the patient comes second.

I'll also admit that my opinion was further skewed by the wealth of poor data collected by various "satisfaction" surveys that using a sampling that would be laughed at by any respectable researcher. We see more than 200 patients per day. One month our sample was derived from a sum total of 14 patient responses. Hard to make valid conclusions with data that is derived from <1% of total patients.

Needless to say, as I mature in my practice, I have come to realize that there is a lot of truth to the statement, "They don't care how much you know until they know how much you care." With that in mind, I want to share some key points from a nice review of customer satisfaction that I stumbled upon from the Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America.

So why pursue a goal of having more satisfied patients?

There are multiple demonstrating benefits from hospitals which perform better:

-Staff morale improves

(Turnover decreases, work is more enjoyable)

-Malpractice risk decreases

(Happy patients sue less frequently)

-Patients respond better to treatment

(Patients follow instructions when they believe that they received good care)

-Hospital finances improve

(Patients recommend the facility and will come back)

The list is pretty impressive. I'd be happy with improvement in one of those categories! So we know that happy patients can bring us happiness, but how can we improve the current quagmire that is emergency medicine?

Obviously, you know your local environment best. Each department will need to tailor a program to its needs. The first step is figuring out those needs: what is the goal you want to strive for? If you already have a program, great! Hopefully you've been keeping tabs. The data gleaned from your surveys can highlight areas in need of immediate attention. What if you haven't kept tabs? Look at complaints, get staff input, administrative input, and use good ol' common sense.

Leadership will be vital. You'll be attempting to change something fundamental about emergency care: our culture. First, get the key players on board: administrative, nursing, and physician leaders. Don't forget the "leaders" within the ranks who may not formally hold a title.

As the leader, you'll be tasked with the following:

-Setting goals

-Modeling and insisting on specific behavior

-Monitoring the behavior and progress towards the goal

-Delivery of rewards and recognition for good performance

Goals take on two forms: philosophic and specific. The philosophic goals helps set the vision for the change, the specific gives the down and dirty expectations and guidance for attaining the vision. Remember to involve the staff. Using goals that they create will help promote buy-in.

Some specific examples:

-Answer all phone calls within X rings

-Door to Doc of X minutes or less

-Door to discharge of X hours or less

-Door to bed of X hours or less

-Each patient will be re-evaluated by a provider every X minutes

Once you choose your goals, it will be up to the leadership to hold people accountable. Some people will resist. Giving that person an exemption will deep six any cultural change before it even has a chance.

Educating the staff will be important. Everyone will need to learn to modify their behavior: physicians, nurses, registration, techs, transporters, housekeeping, etc. The success of your program will depend on universal participation.

Remember to reward the people who contribute. Publicly acknowledge them, give bonuses, a parking spot, etc.

Remember the need for a scoreboard. Even if you missed the first half of a game, you know who's winning by looking at the board. So it is with the staff: they need to know where they're at in order to improve. Publish your results widely: newsletters, emails, bulletin boards, etc. Let patients know too. Success is contagious.

Invariably, there will be some people who choose not to come on board. Once they become obvious, they will need to be removed. Letting them stay within the department will create a division amongst the staff and hurt your chances of success.

There are tools available to help you succeed:

Scripting: developing specific comments for registration, nursing, and even docs can help diffuse anger and demonstrate an attitude of caring.

Patient advocate: This person can make sure that patients who are waiting are up to date with an explanation. They can also help keep the patient comfortable while waiting.

Surveys: You can't change without data. Develop your own, and distribute them widely. The more the merrier. Don't forget to allow family members to fill them out as well.

Call Back System: This tool can help to salvage what may have been a negative impression. You can target specific conditions: Against Medical Advice discharges, left without being seen, etc.

Patient Satisfaction is a worthy goal to persue. It's not easy, that is obvious from our day to day practice. Start by being honest with yourself. Would you want your mother, father, spouse, or child to receive the same care given to the majority of the patients waiting in your waiting room. If you answered no, then step up, become a leader, and promote the improvement that is within your reach.

Reference:

K Worthington. Customer Satisfaction in the Emergency Department. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 22; 2004: 87-102. PMID: 15062498

Friday, April 15, 2011

Better Consultations

A while back a reader asked the following question:

"How do you get them to buy in? as a resident in a surgical specialty, I'd love the EM residents to give better referrals, but often they want nothing more than to sell the patient and move the meat."

This immediately made me think of a lecture given by Emergency Medicine Superstar Chad Kessler. He actually has a research paper on the way studying the effect of his approach that I'm looking forward to reading. In the mean time, I'll settle for listening to him lecture, repeatedly, again and again, on consultation skills. In his lecture, he offers up some consultation pearls that we would all benefit from learning:

The Five "C's" of Consultation

1. Contact: This is where you call your consultant. Before picking up the phone, make sure you need the consultation. I'm currently a dedicated night doc. When admitting a patient to a medical service, the accepting physician will often ask me to "consult" service x,y, or z. Knowing when to simply write an order for a "routine" consultation versus calling each service in the middle of the night goes a long way towards improving your relationship with each service. When you call appropriately, they begin to recognize that when you call, you need them.

When first making contact, make sure to identify yourself and get their identity as well.

2. Communicate: Once you've made contact, tell them about the patient. The level of detail will vary by specialty. Surgery often needs a one liner while medicine wants a thorough review of the patient.

3. Core Question: Here's the money issue: What do you need? Be as specific as possible. "I need you to admit this patient for fluids and antibiotics," or "I need you to take the patient for emergent cardiac catheterization."

4. Collaborate: Let your consultant digest the information presented and respond with their needs. They may need you to order additional tests, call in the cath team, etc. I've found that this are is where the consultation can quickly break down, especially with the uber-specialists. Their plan may deviate from what you believe the patient needs. You may need to take a quick time out and engage in some shared problem solving. I find this to be most true when they're asking for a test to "stall" the need to see the patient.

For example:

"I have a patient with a fever, back pain, and loss of sensation in the L4 distribution who I think has an epidural abscess. I need you to come and evaluate him for operative drainage."

"Order the MRI and call me back after the results."

Unfortunately, this behavior delays the needed evaluation.

Shared problem solving allows you to advocate for the patient and get them to the person they need to see. For example: "How about you send your resident or PA down to get a quick baseline neurologic exam while I order the bed, the MRI, and antibiotics after a set of cultures."

5. Close the loop: Take the time to repeat the plan back. Letting them hear it allows for correction of errors or the addition of something that they may have forgotten. Make sure to take the time to document the date, time, name, and nature of your conversation.

Another important point that Dr. Kessler makes is the need to practice. Just like intubation or suturing, consultation is a skill. To improve this skill, we need to take the time to practice. As teachers, we can help our residents with a "practice run" so that they don't end up frustrated on the phone. With luck, this short list will help to ease the frustration felt with difficult consultations.

A Practical Checklist?

It seems like checklists are the "in" thing in patient safety right now. It makes sense; follow this list of things and you won't hurt patients. The problem is, they only work when you use them.

While doing some background research on checklists in prehospital settings, I found this gem in the open access Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation, and Emergency Medicine. The article is the print version of an oral presentation, so it isn't "science" but it is practical. Prehospital airway management is a hotbed of controversy right now. The data seem to point to worse outcomes, delays to definitive care, and decay of skills. With all of these problems, anything to make the procedure safer is a welcome addition. Enter the "checklist."

This group of prehospital providers created a novel approach to their airway management. They took a disposable plastic sheet and printed it up with the following graphic:

Notice anything cool? While it still has a text driven checklist (on left), the visual representations offer a rapid and convenient way to prepare for intubation.

Their checklist approach is broken into the following areas:

Pre-anesthesia checklist

Monitoring:

Equipment:

Drugs

Staff

It would be easy to replace their text with the more familiar "P's" of intubation:

Preparation

Positioning

Preoxygenation

Pretreatment

Push the Drugs

Placement with Proof

Post-Intubation Management

On the far right you'll also notice a box for induction medications and maintenance medications.

The thing I really like about this list is the visual representation of the equipment. Just looking at it, I believe that it would really decrease the time in the "preparation" phase. Look at what it includes:

Equipment for bag ventilation: oral and nasal airways

Drugs for the procedure (I would like to see these boxes include dosing guides for the common medications)

Equipment for intubation:

2 laryngoscope handles and blades

2 different sized endotracheal tubes

syringe

tube holder

qualitative end tidal CO2 detector with BVM connector

Backup Equipment:

Bougie

LMA

This is HUGE. How many of you out there really take the time and get your backup equipment out before you need it? This demonstrates true foresight.

The only thing that I see missing is the suction.

When working clinically by myself or with the residents, I'm constantly running through a little mental checklist that includes most items on the above list. Being able to pull out a little plastic sheet that has the list already prepared would free my mind up to think ahead and address other important issues with the sick patient in front of me. I can easily see how this has potential to really make both prehospital and emergency intubations safer.

Below is a video demonstration of the checklist in action:

Reference:

A pre-hospital emergency anaesthesia pre-procedure checklist |

Thursday, April 7, 2011

Great Video for Those Beginning Academic Careers

I was perusing my stack of journals the other day and came by a "Dynamic Emergency Medicine" Article in Academic Emergency Medicine. Typically this section contains useful videos about new procedures and has a very heavy ultrasound slant.

What I found instead in this particular journal was a link to a 40 minute video interview of some of the leaders in Emergency Medicine, people at the leading edge of the bell curve. It's a goldmine of good advice for those with interest in becoming a better academic physician.

Take a look and let me know your thoughts!

Interviews with Leaders in Emergency Medicine from Academic Emergency Medicine on Vimeo.

What I found instead in this particular journal was a link to a 40 minute video interview of some of the leaders in Emergency Medicine, people at the leading edge of the bell curve. It's a goldmine of good advice for those with interest in becoming a better academic physician.

Take a look and let me know your thoughts!

Interviews with Leaders in Emergency Medicine from Academic Emergency Medicine on Vimeo.

Friday, April 1, 2011

So You Want More Feedback?

Learners, do you want the truth? Can you handle the truth? In order to receive better feedback from your teachers, you need to take an active part in the process. Here's how:

1. Remember that not all feedback is positive. You need demonstrate a higher level of maturity and self awareness in order to improve.

2. Create your own learning goals and share them. If your teacher knows what you want to learn, they can provide more focused feedback. Don't forget to ask your supervisor for input when creating goals in order to keep you goals realistic.

3. If you're not getting feedback, ask for it. Emergency physicians are action oriented and a passive leaner will get left behind.

4. Clarify. If your teacher says, "You did a great job today," don't be satisfied with your performance. Ask them what you did well and what needs improvement. You won't improve if you don't know where you need improvement.

5. If you get some negative feedback, understand that it is meant not as a personal attack, but an opportunity to improve. Find out from you teacher what the issue is, why it is an issue, and what you need to do about it. If there is an interpersonal issue (rare occurrence) with the teacher, ask your advisor to help you work through the issue.

6. Don't forget to discuss your success as well as what needs improvement. You don't want to lose those skills that you do well.

7. You are probably your harshest critic. Don't be too hard on yourself. Take the credit when you do something well.

8. Be aware of yourself. If you are feeling stressed, rushed, or simply tired, don't be afraid to ask to reschedule for a time when you have your mental faculties in line.

Your teachers want you to succeed. Sometimes we're equally rushed or simply afraid of giving you the advice you need. Following the above list will help us maximize your potential.

Reference:

Feedback in Clinical Medical Education: Guidelines for Learners on Receiving Feedback. JAMA. 1995; 274(12): 938.

Failing at Feedback?

In the last post, we discussed a some background and general tips on feedback, focusing on the seminal article by Jack Ende, MD. Unfortunately, despite all of the hype and hoopla surrounding feedback skills, learners still complain about not receiving enough feedback.

Problems with feedback identified in some studies include:

Too teacher-centered

Too much positive skew

Low cognitive level (fails to engage learner)

So why are we failing at feedback? Perhaps the problem lies with the learner and not the teacher. In a 2009 article titled "Why Medical Educators May Be Failing at Feedback" Bing-You and Trowbridge offer an alternate view on our failure and suggestions for improvement. In their article, they highlight 3 key problems with the learners:

1. Poor ability for self reflection

2. Overpowering influence of affective reactions to feedback

3. Lack of adequately developed metacognitive capacities

Lets take a look at each of these.

Physicians are notoriously bad when it comes to self-reflection. We tend to overestimate our abilities. Just look at the difference between pilots and surgeons on the perception of the effects of sleep deprivation. Even worse, the most deficient performers may be have the least insight into their incompetence.

So what happens when these learners are faced with negative feedback? Pure emotion. The feedback becomes a personal attack. The feedback may trigger emotions such as guilt or anger. The learners unconsciously fall back on ego defenses (denial, distorting information) that prevent a fair assessment of the feedback. Knowing this, it makes sense that learners who have negative reactions to feedback find it less useful.

Learners also need strong metacognitive skills to appropriately process feedback. Metacognition is a the process of "thinking about thinking." Reflection is a valuable metacognitive skill that students can use to critically evaluate the feedback and apply the needed changes. A lack of this skill probably accounts for some of the overconfidence displayed by learners.

So how do we overcome these barriers and get through to the learners?

We need to recognize the affective component of feedback. Knowing that negative feedback will likely invoke some degree of ego-defense, we can use guided reflection to help our students process the information at a metacognitive level. Using follow-up activities to reinforce the positive changes may also help overcome the negative emotions.

There is a growing body of literature about how to teach metacognition. In emergency medicine, we constantly practice procedures. Why not teach metacognition early? Practice with the metacognitive skills students will increase their self awareness and, hopefully, their self-assessment skills.

We need to take another look at feedback. Efforts to improve feedback need to take these learner factors into account. We owe it to our learners and our patients.

Reference:

Problems with feedback identified in some studies include:

Too teacher-centered

Too much positive skew

Low cognitive level (fails to engage learner)

So why are we failing at feedback? Perhaps the problem lies with the learner and not the teacher. In a 2009 article titled "Why Medical Educators May Be Failing at Feedback" Bing-You and Trowbridge offer an alternate view on our failure and suggestions for improvement. In their article, they highlight 3 key problems with the learners:

1. Poor ability for self reflection

2. Overpowering influence of affective reactions to feedback

3. Lack of adequately developed metacognitive capacities

Lets take a look at each of these.

Physicians are notoriously bad when it comes to self-reflection. We tend to overestimate our abilities. Just look at the difference between pilots and surgeons on the perception of the effects of sleep deprivation. Even worse, the most deficient performers may be have the least insight into their incompetence.

So what happens when these learners are faced with negative feedback? Pure emotion. The feedback becomes a personal attack. The feedback may trigger emotions such as guilt or anger. The learners unconsciously fall back on ego defenses (denial, distorting information) that prevent a fair assessment of the feedback. Knowing this, it makes sense that learners who have negative reactions to feedback find it less useful.

Learners also need strong metacognitive skills to appropriately process feedback. Metacognition is a the process of "thinking about thinking." Reflection is a valuable metacognitive skill that students can use to critically evaluate the feedback and apply the needed changes. A lack of this skill probably accounts for some of the overconfidence displayed by learners.

So how do we overcome these barriers and get through to the learners?

We need to recognize the affective component of feedback. Knowing that negative feedback will likely invoke some degree of ego-defense, we can use guided reflection to help our students process the information at a metacognitive level. Using follow-up activities to reinforce the positive changes may also help overcome the negative emotions.

There is a growing body of literature about how to teach metacognition. In emergency medicine, we constantly practice procedures. Why not teach metacognition early? Practice with the metacognitive skills students will increase their self awareness and, hopefully, their self-assessment skills.

We need to take another look at feedback. Efforts to improve feedback need to take these learner factors into account. We owe it to our learners and our patients.

Reference:

Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009 Sep 23;302(12):1330-1. PMID: 19773569 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

Friday, March 18, 2011

What is the Deal with Feedback?

"Anyone willing to be corrected is on the pathway to life. Anyone refusing has lost his chance."

-Proverbs 10:17

"We are training a group of physicians who have never been observed"

-Ludwig Eichna, MD

Today marks the first of a series of posts on feedback. I had initially planned on a single post but as I dug deep into the literature, I realized that there is far too much good stuff for a single post.

Feedback is such a hot topic in the medical education literature. We pay a lot of attention to it, yet students still rate our feedback skills as mediocre at best. They want feedback, and from what I've seen clinically, they NEED feedback. Unfortunately, as in many educational endeavors, we haven't been trained in appropriate techniques. Even with training, learners will often miss the fact that they've even received feedback.

Feedback is an essential component to improvement. Without insight into our failures and successes we fall into a routine and make the same errors over and over.

So what is feedback and why does it matter?

August 12, 1983: A Call to Arms. It was on this day in JAMA that Jack Ende, MD, published what is possibly the most referenced article on feedback. His work is still relevant today.

He defines feedback as "An informed, nonevaluative, and objective appraisal of performance that is aimed at improving clinical skills rather than estimating the students personal worth."

The above definition highlights some keys to good feedback:

Informed and objective: Feedback is based upon first person observations of skills, behaviors, and attitudes. Without this first person account, a student will tend to discount the value of the feedback.

Nonevaluative: Feedback is much different from evaluation. Evaluation is a summative judgment that occurs at the completion of a period of time. Feedback is formative; it allows the learner to identify areas in need of improvement in real time without fear of a negative evaluation.

Aimed at improving clinical skills: The skills we need to master to become a competent physician are so vast that it is almost overwhelming. Feedback helps to accelerate the process by offering tips and pearls for improvement.

Dr. Ende also includes his guidelines for giving feedback within the article.

Feedback Should:

1. Be undertaken with the teacher and the learner working as allies, with common goals

Start each shift by finding out what skills your learner wants to focus on. This gives the learner an active role and allows you to create a metric for feedback later in the shift.

2. Be well timed and expected

Feedback should be expected by the learner, or better, solicited by the learner. An understanding on the teacher part is needed to avoid times when the learner is not overly stressed.

3. Based on first hand data

The best person to provide feedback is the person who observed the trainees performance. This is often the same person experienced enough to make relevant observations of performance.

4. Regulated in quantity and limited to behaviors that are remediable

Keeping feedback short and limited to only 1-3 behaviors or skills needing improvement allows for the learner to make the needed corrections without overwhelming them with information.

5. Phrased in descriptive, nonevaluative language

Care should be taken to word the feedback effectively in a nonjudgemental fashion. "Your differential did not include _____" is much better than "Your differential is limited and needs a lot of work."

6. Deal with specific performances, not generalizations

How often do you hear "Good job today" as the only feedback a student gets? While good for the individual ego, this kind of feedback is useless when if comes to effecting improvement. Focus on "actions" in order to provide more effective feedback. Statements that allow for psychological distance are helpful as well. For example,"The choice of sux for a paralytic in this dialysis patient didn't account for the possibility that he may have hyperkalemia" is better than "You completely failed to consider the contraindications to sux when performing RSI on this patient."

7. Offer subjective data, labeled as such

When offering subjective data, make sure to use "I" statements, especially when offering personal opinions or reactions. Consider the following: "While watching you perform the history, I felt that you were uncomfortable addressing the sexual history" vs "You looked uncomfortable addressing the sexual history." The latter statement could give the learner the fear that their discomfort was on show for all to see.

8. Deal with decisions and action, rather than assumed intentions or interpretations

By focusing on the decisions or actions, and not the learner per se, the learner and teach can review the effects of the decision without assigning blame and inducing psychological protection mechanisms that would prevent to learner from accepting the feedback.

Feedback is an essential part of learner improvement. While Dr. Eichna identified the problem with the lack of observation more than 30 years ago, he missed the fact that even when observed, faculty fail to offer insights for improvement. This is where the value of good feedback skills becomes mandatory. Without it, mistakes continue uncorrected, sound practice is not reinforced, and the students rarely become clinically competent. Feedback is hard, but not as hard as some believe. With practice, these skills will become second nature and you will make a difference in the care of thousands of patients.

Reference:

Reference:

Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983 Aug 12;250(6):777-81. PMID: 6876333 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

Friday, March 11, 2011

Becoming a Better Mentor

Mentor and Telmachus, son of Odysseus

Mentoring has been identified as a critical factor in achieving success in many fields. Unfortunately, like many skills related to the education of healthcare professionals, mentors rarely receive any training in how to become a better mentor.

This is unfortunate. Faculty who have had an effective mentor report the following:

-Increased confidence

-Increased research productivity

-Higher career satisfaction

-Meaningful involvement in academic activities

-Development of close collaborative relationships

With all of the above benefits, it's surprising that their isn't more attention paid to developing more effective mentors. As with many of the skills, we're often left to figure it out ourselves.

So what skills are needed to be a better mentor?

While not an exhaustive list, some traits identified with being an effective mentor include:

1. Being knowledgeable and respected in their field

As I identify mentors for myself, this is a key trait that I look for. But what about the typical residency mentoring structure? Residents are often assigned to a random faculty member based on volume and availability. One change we made to our program was to allow residents to self-select after the first 6 months. Residents can also change mentors as they see the need. As a mentor, I know that I constantly need to continue to improve my expertise within my chosen niche.

2. Being responsive and available to their mentees

This can be a difficult task with the demands of clinical emergency medicine. We're often at work while the rest of the world goes to dinner, watches TV, and heads to bed. Setting aside dedicated time to meet with the mentee goes a long way. I try to make myself available on the residents education day. They're already going to be around, so why not take the time to sit down with them and see how they're doing.

3. Interest in the mentoring relationship

This trait is somewhat of a no-brainer. Why would you participate if you aren't interested? Take a deeper look. Many times we enter the mentoring relationship with full intentions to make the relationship work. While our initial interest may have been high, sometimes life happens and we let the relationship stagnate. We need to constantly monitor the effectiveness of our mentoring relationships and know when to direct our mentees on to a more effective mentor if we can no longer meet our end of the bargain.

4. Being knowledgeable about the mentees capabilities and potential

This can only be acheived with time dedicated to learning about the mentee. Fortunately, working with residents offers ample time to learn about them and observe their capabilities first hand. When initiating a mentoring relationship, it is helpful to dedicate at least 30 minutes of time to a relaxed interview with the mentee to delve deeper into their interests, goals, and to learn about what they desire from the relationship.

5. Motivating mentees to appropriately challenge themselves

I constantly struggle with this skill. Unlike teaching, where the challenge comes from the subject matter, challenging a mentee is more difficult. How do you challenge your mentee? I try to offer my mentees involvement in projects that come along. Follow this up with your expectations, and you have issued the challenge that they need for professional growth. Don't forget to offer support in additional to challenge. It take just the right amount of each to grow.

6. Acting as an advocate for their mentees

Failing to act on this trait came close to ending my academic career. Early in my first year out of residency, I was mentoring a new intern who was having academic and professional difficulty. In the ensuing months, I had a seat at the table for many remediation sessions. Unfortunately, the whole situation became quite hostile. What I should have done better was to take my concerns up the chain of command. If I had been a better advocate for my mentee the situation would likely not have progressed as far as it did. Like many things in life: Live and Learn. As mentors, we owe it to our mentees to be their advocates. If they need resources to get research done, we can help them get it. If they're having difficultly, we can level the playing field to make sure that each party has equal representation at the table.

Mentoring is a difficult skill to master. With all of the demands of being a clinician and faculty member, it isn't surprising that our skills are mediocre at best when it comes to being a mentor. The above simple traits can help to guide you in the right direction as you continue to improve as a mentor to your students and residents.

If you're already an expert, what traits do you feel are needed to be effective?

Reference:

Ramani S, Gruppen L, Kachur EK. Twelve tips for developing effective mentors. Med Teach. 2006 Aug;28(5):404-8. PMID: 16973451

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

Toxic People

Do you ever have to work with people that just drain the life out of you? I'm not referring to patients, but to those colleagues and consultants that you have to deal with on a daily basis. I recently had the opportunity to sit in on a lecture given by Marsha Petrie Sue, author of Toxic People and The Reactor Factor. I think we can all benefit from an understanding of her approach to reading people and managing conflict.

So who are the players?

Steamrollers: These are the bullies. They come off as overbearing and try to make you feel small

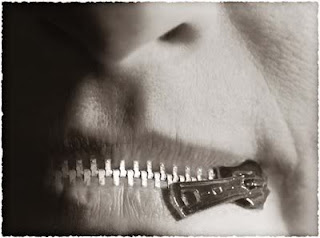

Zipper Lips: "Verbal Anorexic." They think of their knowledge as power and don't share it

Back Stabbers: People that are in it for themselves, always looking for an advantage

Know-It-All: These guys LOVE the limelight and have a hard time letting other contribute

Needie-Weenie: People with this type of personality are fearful of change and have a need to be liked

Wine and Cheeser: Nothing is ever right to these people. They do make good Devil's Advocates though. . .

And how do you deal with them?

First, reflect on whether you react or respond. You need to take the time to mentally step back and respond. Reacting just gets in the way of progress.

Since Steamrollers try to be overbearing, first, use their name. A persons own name is the most recognizable word in their vocabulary. This technique stops them in the tracks and opens their ears.

Example: "Rob, as I was saying, to fix this we could _______."

To deal with a Zipperlip, you need to change the rules they like to play by. Call them on their habit. Give them deadlines but be willing to wait, and wait, and wait, if they decide not to respond.

Example: "I expected you to respond by now, we can schedule a time to meet this afternoon instead if it is better for your schedule." This puts the ball into their court. Resisting involvement now takes time away from them until they participate.

Back Stabbers are best dealt with in public. Try to call them out on their behavior.

Example: "That did sound like you were serious. Is this something we need to address? Does everyone else feel this way"

Know-It-Alls: In this case, busy hands are happy hands. Give them a task and they're in seventh heaven.

Example: "Rob, you're the expert in this case. Why don't you help me understand where you're coming from. Also, can you help me keep track of all of the other ideas offered today?"

Needie-Weenies: In order to get buy in, you need to allow this type of personality to lead some of the change.

Example: "I'm glad that you basically agree with the curriculum updates. What part could be most improved?"

Wine and Cheesers: These guys just love to complain. To deal with them, call their issue and offer to help.

Example: "Are you looking for specific solutions to the call schedule mishap, or do you just want me to look into the problem with you?"

These are just a few of the many methods for dealing with the various types of personalities. A better understanding of the players helps to make teams more effective and improves the workplace culture.

Now that you know these quick tricks, what is your type? I personally think that I'm a know-it-all and when I don't feel appreciated, I can become a zipperlip. You?

Also, what techniques have you found helpful in dealing with the various types?

So who are the players?

Steamrollers: These are the bullies. They come off as overbearing and try to make you feel small

Zipper Lips: "Verbal Anorexic." They think of their knowledge as power and don't share it

Back Stabbers: People that are in it for themselves, always looking for an advantage

Know-It-All: These guys LOVE the limelight and have a hard time letting other contribute

Needie-Weenie: People with this type of personality are fearful of change and have a need to be liked

Wine and Cheeser: Nothing is ever right to these people. They do make good Devil's Advocates though. . .

And how do you deal with them?

First, reflect on whether you react or respond. You need to take the time to mentally step back and respond. Reacting just gets in the way of progress.

Since Steamrollers try to be overbearing, first, use their name. A persons own name is the most recognizable word in their vocabulary. This technique stops them in the tracks and opens their ears.

Example: "Rob, as I was saying, to fix this we could _______."

To deal with a Zipperlip, you need to change the rules they like to play by. Call them on their habit. Give them deadlines but be willing to wait, and wait, and wait, if they decide not to respond.

Example: "I expected you to respond by now, we can schedule a time to meet this afternoon instead if it is better for your schedule." This puts the ball into their court. Resisting involvement now takes time away from them until they participate.

Back Stabbers are best dealt with in public. Try to call them out on their behavior.

Example: "That did sound like you were serious. Is this something we need to address? Does everyone else feel this way"

Know-It-Alls: In this case, busy hands are happy hands. Give them a task and they're in seventh heaven.

Example: "Rob, you're the expert in this case. Why don't you help me understand where you're coming from. Also, can you help me keep track of all of the other ideas offered today?"

Needie-Weenies: In order to get buy in, you need to allow this type of personality to lead some of the change.

Example: "I'm glad that you basically agree with the curriculum updates. What part could be most improved?"

Wine and Cheesers: These guys just love to complain. To deal with them, call their issue and offer to help.

Example: "Are you looking for specific solutions to the call schedule mishap, or do you just want me to look into the problem with you?"

These are just a few of the many methods for dealing with the various types of personalities. A better understanding of the players helps to make teams more effective and improves the workplace culture.

Now that you know these quick tricks, what is your type? I personally think that I'm a know-it-all and when I don't feel appreciated, I can become a zipperlip. You?

Also, what techniques have you found helpful in dealing with the various types?

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

The Microskills

It's a typical Saturday night in the department. You're busy. I mean really busy; the "too busy to make a run to the bathroom and empty your overly distended bladder" busy. Your resident comes up to you with their next patient. At first, you think of just hearing out the chief complaint, telling them what to order, and moving on to the next patient. Fortunately, a voice in your head reminds you that there is a better way, a way to promote a morsel of learning despite the challenges stacked before you. Enter the microskills.

The microskills model of teaching, also referred to as the "One Minute Preceptor," is a series of easily performed steps that allow you to maximize a teaching encounter when time is precious. The steps are:

1. Get a commitment: I love using this step to shorten the presentations from my learners. Too often, they get lost in the forest when presenting a case. Simply stepping back and asking, "What do you think is causing their symptoms?" allows me to hone in on the important parts of their presentation. I can then focus my questions to help me understand why they are concerned about possible conditions on the differential that they have created. "I don't know" is not an acceptable answer.

2. Probe for supporting evidence: The follow up. Once they take a stand, you're able to ask the why and what if questions. The more direct questioning focuses them on the task at hand and allows you to understand the history a little better as well as determining the learners decision-making process.

3. Teach general rules: The time to teach a mini-lecture is not when time is limited. Instead, focus on a key point of the case, whether a historical factor, workup issue, or interpersonal problem and teach short and succinct pearls.

4. Reinforce what was done right: Reward the learner for their efforts. Point out the good catches on the history or exam, congratulate them on making the correct diagnosis or picking the most effective workup.

5. Correct mistakes: Feedback is always critical. Point out errors in their decision-making and explain methods to correct them in the future. Point them toward resources for future learning.

The microskills have been employed in clinical teaching for over 20 years now. While effective use of the skills takes more than the allotted "one-minute" advertised by the other name, the skills are quite helpful at keeping the teaching encounter short and focused. When it gets too busy to teach, reach into your armamentarium for this quick and easy teaching tool. You'll be glad that you did.

Reference:

Parrot S, Dobbie A, Chumley H, Tysinger JW. Evidence-based office teaching-the five-step microskills model of clinical teaching. Fam Med. 2006 Mar; 38(3): 164-7. PMID: 16518731

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)